Back in the early days of my business I had a very unhappy customer and, to make matters worse, the customer was a lawyer, not a good combination. Our lawyer friend brought me an MGB with its engine, in boxes, with a whole bunch of new parts and asked me to reassemble it and put it into his car. He had had various parts of the engine rebuilt including the carburetors and the cylinder head, which sported brand new bronze valve guides but had decided that he lacked the time, or skills to complete the job himself. After negotiating a price for the job and using his parts, I reassembled the engine and put it into the car. It ran well and he was very happy when he picked the car up on a Friday night with a view of driving it about 180 miles directly up to his cottage. I was more than a little surprised upon my arrival at work the following Monday morning to find the car dropped in the driveway of the shop with a note written in a distinctly cool tone on the driver’s seat and a very seized engine. It turns out that there is a bit of a hill on the highway route to his cottage and seconds after cresting this hill there was a loud bang from his newly rebuilt engine, followed immediately by a squealing of tires as that engine seized and the rear wheels locked up. It must indeed have been a little frightening in the heavy cottage traffic and I could appreciate the reason for the man’s ire.

Various lawyers letters flowed back and forth all of which culminated in a small claims court claim being filed. I disassembled the engine and found that #3 exhaust valve had gone through the top of the piston and caused unimaginable indignities to the rest of the engine. I studied that engine in intense detail before I figured out the sequence of events which resulted in its failure.

Many after market suppliers extol the virtues of the bronze or silicone bronze valve guides that they sell and, although these may wear marginally more slowly than cast iron valve guides, it is my belief that bronze of any type is not an ideal material to use for exhaust valve guides in cast iron heads.

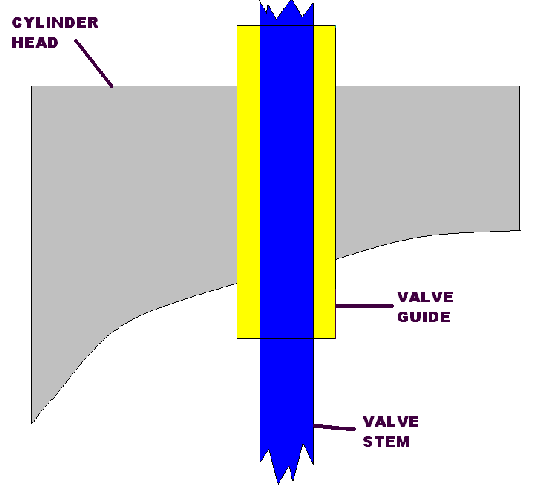

This is a simplified cross section of a guide installed into a cylinder head.

Valve guides are normally a press fit into the cylinder head, that is to say that the guide is very slightly larger than the hole in the head into which it is pressed. The interference, i.e. the difference in diameters, is usually one or two thousandths of an inch. This tight fit is sufficient to keep the guide securely located in its correct position in the cylinder head. Once the guides are installed the inner bore is usually reamed to an exact size to produce, in the case of the exhaust valve, a clearance of around 0.0015 to 0.003” between the valve stem and the guide. This tight fit is necessary to correctly position the valve on its seat and because excessive clearance here can result in hot gasses passing through the space and burning oil in the engine making things all black and yucky.

Now, although I have never stuck my finger into the exhaust gas stream to measure it, I have it on good authority that the gasses exiting the combustion chamber and shooting up the exhaust port have a temperature of the order 1300 – 1500 degrees F. and, under full power, can go as high as 1800 degrees.

If the valve guides are cast iron, the same material as the head, the interference fit of the guide in the head remains constant as the engine heats up or cools down. Bronze, according to my Machinist’s Handbook has a linear expansion per unit length (coefficient of expansion) of 0.00001 per degree F. whereas for cast iron that expansion rate is 0.0000065. In little words this means that, when heated, bronze expands 1.5 times faster than cast iron when heated and it is these different coefficients of expansion which create problems for our bronze valve guides.

If we presume that a particular exhaust valve guide has an outside diameter of 0.75 inches and it is heated from 20 degrees F to 1500 degrees F its outside diameter will increase by 0.011”. Of course the hole in the head will also expand as a result of this temperature increase but, the cast iron has a lower rate of expansion and is cooled by the engine coolant. If the temperature of the cast iron in that area of the head rises to say 500 degrees the hole will only increase in diameter by about 0.002”. The result of all this is that the one to two thousandths of an inch of interference fit of our guides becomes nine thousandths of and inch of interference when things get hot!!

The question arises then as to where does all this expanded bronze material go? Those familiar with the properties of cast iron will be well aware that it is not very elastic so it is unlikely, even give the huge forces involved, that the hole will temporarily stretch to accommodate the expanded guide therefore the only realistic conclusion is that the head constrains that expansion of the guide and effectively compresses it some 0.009”. One can only imagine the forces involved and, can occasionally see evidence of this where cylinder heads are cracked radially around the valve guide holes when bronze guides have been used!!

Amazingly, for the bronze guides to continue to function normally, the bronze must be sufficiently elastic to actually return to its original dimensions as the engine cools and, of course, bronze is another material not given to stretching, or in this case being compressed very much!!

Under normal engine operating temperatures this is actually what happens but, if the exhaust gas temperature become further elevated, things really go pear shaped, literally.

Most fuel systems are set up to provide a slightly rich mixture at full throttle. Aircraft always use a very rich mixture at takeoff power. The reason for this is that the excess fuel will actually cool the induction charge and produce more power than would be the case with a perfect mixture setting. Of course this over rich mixture also serves keep the cylinder head temperatures down a little and prevent detonation. However, as anyone who flies a piston engined aircraft will tell you cylinder head temperatures rise very quickly if you try to get power from an engine when the mixture is set lean.

When this over temperature condition occurs in our cast iron headed car engine the expansion of the bronze reaches a point where the “elastic limit” of the bronze is exceeded.

What the term “elastic limit” actually means is that when a material is deformed beyond its elastic limit the material no longer returns to its original shape when the deforming forces are removed.

Now, going back to our valve guide, when such overheating occurs the guide cannot expand because it is constrained by the cast iron of the head and, as a result, the material of the guide has nowhere to go so is actually radially crushed by its own expansion forces.

You may want to read the previous sentence again.

Of course, with the small clearance between the exhaust valve and its guide, any permanent inward deformation (radial crushing) of the valve guide is, when the guide cools down, going to eliminate this clearance and cause the guide to contract sufficiently to eliminate any clearance between it and the valve stem. Put another way; the valve seizes in the guide.

I have only seen this situation occur in a handful of cases but, as in the case of our learned friend, when it does the results will be nothing short of catastrophic.

In addition to the decrease of the size of hole through the guide where the valve stem is located the outside diameter of the guide is also going to permanently decrease which will result in the guide becoming loose in the head in the areas where it is enclosed by the head material.

Prior to my figuring this problem out I had frequently noticed, when removing worn bronze valve guides from cast iron heads, that there was a distinct step right where the guide protruded into the port and I it took me a few years to put two and two together on that one.

This is what the result looks like.

Of particular interest to performance car owners will be the fact that this problem is more likely to occur in multi-carburettored engines because, in this type of engine, it is relatively common for one carburetor to be delivering a leaner mixture at high throttle without the overall driveability being adversely affected and that leaner mixture will result in substantially higher exhaust port temperatures.

So should one use bronze valve guides? Absolutely, but only if the cylinder head is made of aluminium because, it just so happens, that the coefficient of expansion of aluminium is very similar to that of bronze. If the bronze guides are installed correctly in an aluminium head, they should not suffer from this distortion problem.

If you are rebuilding a cast iron head stick with cast iron valve guides because you never know when a blocked jet, failing fuel pump or an intake manifold gasket leak is going to provide the leaner mixture conditions which will lead to disaster.

Hello Mike, thank you for a very thought provoking article, however, you maybe overstating the dimensional changes and forces involved considering the difference in CTE of the two dissimilar metals. In my case the wall thickness of the valve guide is only 0.066″ and the guide is not exposed to the gas flow in the exhaust port and in fact is flush with the head casting. I do believe, however, that there is some merit in what you are describing in that there could be distortion of the valve guide if the right combination of conditions exist. I am presently rebuilding my Aston Martin DB2 cylinder head which is cast iron and was supplied with cast iron valve guides from the factory. Because cast iron guides are not available for this engine any longer I will consider machining my own at least for the exhaust. Thank you for bringing attention to a subject that most people do not give enough consideration to.

Hi Bruce, thanks for taking the time to read and comprehend my post on bronze guides.

Update as I promised. Steve’s AH3000 head is running like a top with the bronze guides I put in his head I ported for him. – Hap Waldrop