Many, many years ago we had an Austin Healey delivered to the shop on a flat-bed. The car, a 100/6, was missing the right front wheel; not only the wheel, but the stub axle, the brake drum, the wire wheel splined hub and spinner were also MIA. The owner/driver reported that he had hit a substantial pot hole while spiritedly driving down a country road and immediately the right side of the car dropped to the ground and everything went “pear-shaped”, as he put it. Fortunately, he hadn’t been travelling too quickly and, although he had no brakes, had managed to bring the car to a halt before hitting anything significant.

Despite a fairly intensive search, no sign of the missing parts could be found and it was concluded that the wheel had bounced off into the Greater Canadian Wilderness never to be seen again!

The cause of this incident was a failed front stub axle which had broken off just inboard of the inner wheel bearing.

This all happened years before the appearance of the internet but, when I raised the subject at a club meeting, a very interesting discussion ensued regarding the use of bearing spacers between the inner races of Austin Healey front wheel bearings.

The crux of the discussion was whether or not these spacers were necessary and, after all viewpoints were put forward, we were unable to come to a consensus. The pertinent points raised were:

- Many makers of rear-wheel-drive cars do not use this type of spacer, including most American and several British manufacturers.

- If the designers of the Austin front hub assemblies had decided to use spacers then they MUST have had good reason.

- We had all encountered incidences of cracked stub axles.

I have given this subject much thought over the ensuing years and concluded that there most certainly is a reason for using these spacers.

During the process of supplying the required parts and repairing the 100/6 we decided to crack test all the used Healey stub axles of the same type using a penetrant dye method and we were surprised to find that at least 50% had cracks on the lower side just where the other had broken. Fortunately our used parts were all identified as to which car they had been removed from and almost all the cracked ones had been removed from BN2’s. We also checked the left side of the 100/6 in for repair and discovered that not only was it missing the bearing spacer and associated shims but it was also cracked.

The obvious question is, why BN2’s? Because, unlike BN1’s and 100/6’s, BN2’s were not originally fitted with the bearing spacers and shims!

We concluded that the 100/6 had, at some stage, had the front hubs and stub axles changed for a set from a BN2 or perhaps someone just decided that the spacers and shims were surplus to requirements.

We concluded that the 100/6 had, at some stage, had the front hubs and stub axles changed for a set from a BN2 or perhaps someone just decided that the spacers and shims were surplus to requirements.

So why is it desirable to have those spacers?

Well, in simplified terms it is all to do with the diameter of the base. Consider a 4-foot-high stack of bricks. Apply a force to the side of the top brick and it is pretty easy to push over the entire stack.

Now try the same thing with an empty 40 gallon drum which probably weighs about the same and you are going to have to push a lot harder to topple that.

Effectively, what the spacer does is increase the diameter of the base of the stub axle so that when a force is applied the stub axle does not flex or bend as far thus decreasing the possibility of fatigue failure which is defined as: “The tendency of a material to fracture by means of progressive brittle cracking under repeated alternating or cyclic stresses of an intensity considerably below the normal yield strength of the material and is a function of the magnitude of the fluctuating stress.”

You may be able to tell that I didn’t write that mouthful, but in simple terms the further the stub axle bends the more rapid is the onset of fatigue failure.

There is a very interesting photograph taken by Daniel Rubin of Stirling Moss in a 100S retiring from the 1955 Nassau trophy race with a broken stub axle.

The 100S used the same front hub design as the BN2 i.e. no bearing spacers. I often wonder if this incident had anything to do with why B.M.C. reintroduced them.

Incidentally, why didn’t Stirling’s wheel take off into the undergrowth like the one on our 100/6?

The answer is that unlike the 100/6, the 100S had disc brakes and the disc brake caliper held onto the wheel.

Mike, the front bearings are replaced and the proper shims installed with the spacer. It was very interesting to see how .001″ made a difference between too tight and not tight enough.

Another good post, Michael. A couple things:

– To the best of my recollection–I haven’t gotten in there in a while–my BN2 has the spacers. I think it was one of the later cars so maybe they were added at the end of the run? Nothing else about the car makes me think any of the previous owners were particularly diligent or careful with the car (though it was in relatively good shape when we bought it).

– If you don’t have facilities for using a penetrant dye–what us Yankees call ‘magnaflux’–the ‘ring test’ can sometimes suffice. Suspend the stub axle, preferably with wire, and give it a sharp rap with a hammer, wrench, etc. The axle should ring, like a tuning fork, but if you get a dull thud you likely have a crack in the axle. My dad took our stub axles up to BCS to have new bushings installed and reamed, and Dad said Norman Nock was impressed by Dad’s knowledge of the ring test (Dad was an Old School mechanic himself).

– I always assumed if a part wasn’t absolutely necessary the BMC bean counters would have it removed; maybe they realized keeping the spacer, for the BN4s and later cars was cheaper than replacing broken stub axles?

Clarification: Magnaflux and dye penetrant aren’t the same process.

Mike et al., I have no idea how common a practice using the spacer/shim set-up was on British cars, but I do know that my M.G. TC has the same set up, and I think all the T-series M.G.s, and later models were the same. I definitely agree with your argument about the spacer increasing the strength of the stub axle. I have also wondered whether, in addition to in effect increasing the base diameter of the axle, whether putting the stub axle in tension from tightening the nut (without loading the bearings!) also increases its strength. I don’t know that, just wondered. Back to the TC. Years ago a maintenance book was published for the T-series M.G.s that recommended upgrading the front bearings by replacing the standard ball-bearing to tapered roller bearings. The book said that the spacer and shims could then be omitted, per common practice with American cars. What followed over the years was a rash of M.G. front stub axle failures! One enterprising enthusiast profited from this by making up and selling replacement stub axles. That demand has now dropped off as we know the spacers and shims MUST be installed as eloquently described in the Healey (and M.G.) manuals.

Michael –

I thought we had put this issue to bed long ago. The purpose of the spacer is to permit proper loading of the bearings and it has little to nothing to do with strengthening the axle. If I could insert a photo here, I could show exactly how the spacer does its job. The “stack” may have some small effect on the bending stiffness of the axle, but it is not significant enough to be the difference between cracking and not cracking the axle.

I had a structural analysis done by a colleague at work to show that unless the stack is permanently attached to the base of the axle (such as by welding), the bending stress on the bottom of the axle at the base is not reduced to any significant degree.

I remember well our discussion on this subject Steve and would very much like to see how the structural analysis was done and whether it included study of repetitive cyclical stress. (Fatigue stress)

The very fact that BMC reintroduced the spacers and shims on the later BN2’s would tend to indicate that they recognized that they had a serious problem as Len Lord was not one to waste money on unnecessary parts!

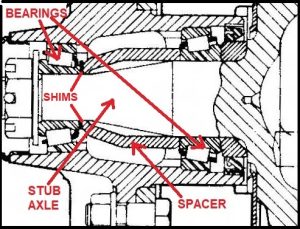

The BN2 Workshop Manual Supplement has some interesting gobbledygook on the subject wherein it states:

“On later models a distance piece is fitted between each bearing (See insert, Fig 1). When adjusting make sure that the distance piece is a firm fit in the hub by packing with the necessary shims. These shims are selected to eliminate shock, therefore do add not too much thickness so as to cause undesired preload of the bearings.”

Despite having read that sentence many many times I really have no idea what it means!! Adding too much thickness removes preload from the bearings and makes them too loose. I think whom wrote that was in a hurry to get off to the pub!!

Michael

Looks like you have thought this situation through. Any movement of the bearings along the stub axle ie insufficient spacer and / or shims will induce a repeating hammer load on the stub axle that would seem to lead to failure of the weakest link. It will beat the snot out of the bearings or the supporting structure, the stub axle.

There is a possibility that there was a large batch of faulty stub axles produced but over the last 58 years of involvement with these cars it has not been mentioned to me previously.

P

I’ve never heard anything about a bad batch of stub axles either Perry.

I’m very confident that the lack of the bearing spacer can be a major contributing factor in stub axle failure.

It should also be remembered that an out of balance wheel, even with correctly adjusted bearings, causes a cyclical load on the stub axle which over time will most definitely result in metal fatigue.